3D-printed sensors to tackle milk fever

Milk fever, or hypocalcaemia, in lactating cows has a significant economic impact on the dairy industry, with losses amounting to thousands of dollars per farm annually.

Farmers find it challenging to identify asymptomatic subclinical hypocalcaemia (SCH) in transition dairy cows, although monitoring SCH in milk samples can expedite treatment and improve the health, productivity and welfare of dairy cows.

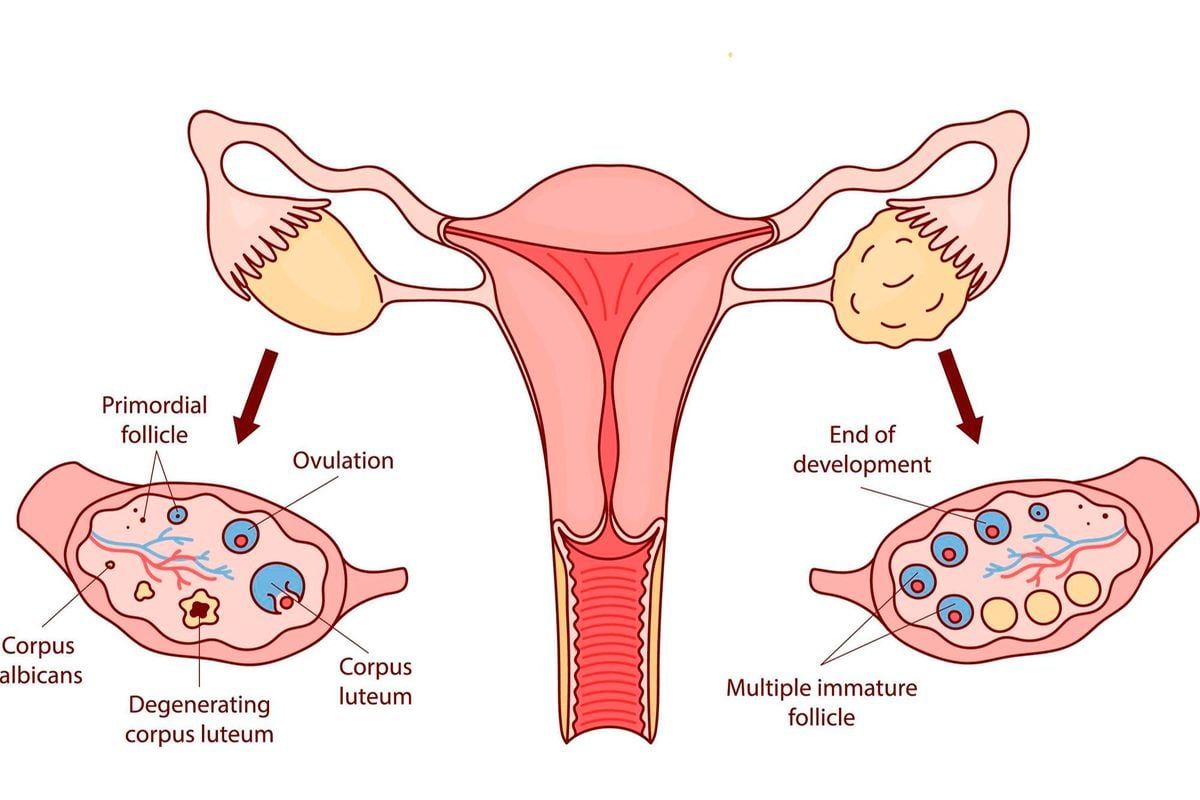

SCH occurs when calcium levels in the blood fall below normal, and it can affect nearly half of mature dairy cows and a quarter of first-time calvers. The condition compromises muscle and nerve function, leading to reduce feed intake, lower milk production and increased susceptibility to other diseases.

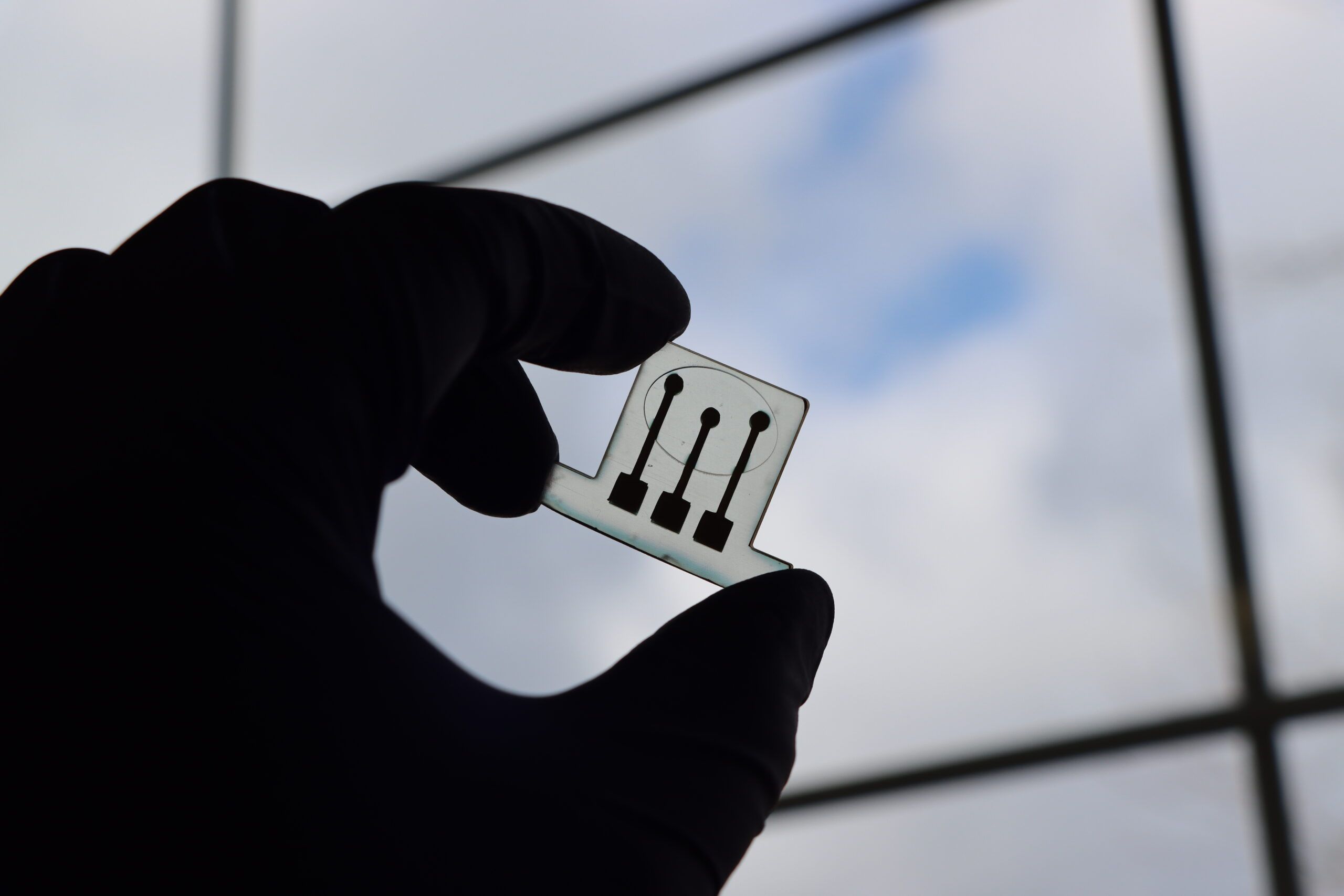

Current diagnostic tools rely on blood sampling and lab-based analysis, which are costly, time-intensive and impractical for routine farm use. Researchers at the School of Animal Sciences at Virginia Tech in the US wanted to develop an attomolar-sensitive sensor using extrusion 3D-printed sensing structures to detect the ratio of ionised calcium to phosphate levels in milk samples.

The 3D-printed sensor features intricate microstructures and a unique wrinkled surface creating using a solid-contact ion-to-electron transducer. These design elements enhance the surface area, enabling rapid and highly accurate detection of milk ions.

The diagnostic device can identify SCH in as little as 10 seconds with attomolar-sensitivity and, unlike bulky and expensive lab equipment, the sensor produced at Virginia Tech, with a solid-state feature, is portable and can be integrated with milking machines or farm pipelines. Farmers can now test milk samples on-site, eliminating the need for invasive blood tests or transporting samples to labs.

Lead researcher at Virginia Tech, assistant professor Azahar Ali, said the innovation bridges a long-standing gap in dairy diagnostics.

“Farmers have traditionally relied on either expensive commercial analysers or subjective assessments based on visible symptoms like weakness or difficulty standing. Neither approach is sufficient for detecting SCH early enough to prevents its cascade of complications. Our 3D-printed sensor not only makes early detection feasible, but also democratises access to advanced diagnostics,” said Ali.